Could you please describe your workflow and working methods on a specific project that you have done recently?

We recently worked on a challenging project with a rural health organization in the Wimmera region in rural Victoria, Australia.. The emergency services across that region of the country were pretty fragmented. There were people working at the emergency rooms at the hospital, primary care physicians, social services, the ambulance drivers and all the different people in-between. Each one of them was working on improving their own services to improve patient outcomes. But a lot of those different organisations were doing so in silos or independently so weren’t really thinking about how those things work together, nor coming to that problem from a patient-centered perspective. So our team was brought in to help facilitate them getting together for the first time, everybody in the same room from all these different disciplines - nurses talking with senior executives talking with ambu-drivers and everyone, to say: alright, where are the main points in this process, where are the opportunities and how are we going to work together to solve these problems? We did that over a 2-day workshop together with our business designers and kind of expert facilitators. And there was a big part of visual design in this project as well, because we needed to communicate some really complicated concepts.

This is how we are doing it across almost all of our projects. We do this quite heavy research and workshops and working with clients, we need to communicate that output somehow. And that is generally where I come in. So, for this particular project, I had to get a quite deep understanding of what was going on, because we needed to create these journey maps to map the service ecosystem.

All the different pieces and all the different players. So visual design was really helping to map a complex system. It’s one thing to talk about it and have all those people in the room but having a visual map that you can respond to and communicate to helped everybody get on the same page, using the same language and everybody had the same picture in their head because they were literally looking at it on the table. This is the power of service design and business design, coming together with communications design to say, “alright this is how we are going to solve this problem, and we are going to solve it effectively using these tools, we’ve got some creative workshop tools, we’ve got some visual tools and we’ve got post-it notes everywhere and all these types of things. So at the end of that project, there was kind of a game plan that came out of it. But a lot of the next steps were happening already during the workshop, We know this from talking to people as they’re walking out the door. So there wasn’t a lot of followup from our side because that was already happening. So we’ll see. They are improving their system right now working out some of the things that came out of the workshops.

the interview in full- length will be publishedin a book after our journey.stay tuned – #thewalzhappens

in fitzroy, one of the creative neighborhoods of melbourne, we met kelsey schwenk, engagement director and jacob zinman-jeanes, senior designer at THICK, a strategic design agency. THICK’s mission is to design human-centric products and experiences that benefit the world by generating positive social, environmental and business outcomes. they partner with progressive businesses and organisations to reimagine their strategies, products and services for a brighter future.

| date: | april, 2015 |

| city: | melbourne |

| interview with: | kelsey schwenk / jakob zinman-jeanes |

| www: | studiothick.com |

"In design, there are career paths that aren’t the traditional ones, you can have an impact, even if you are just coming out of school, to make the world a better place."

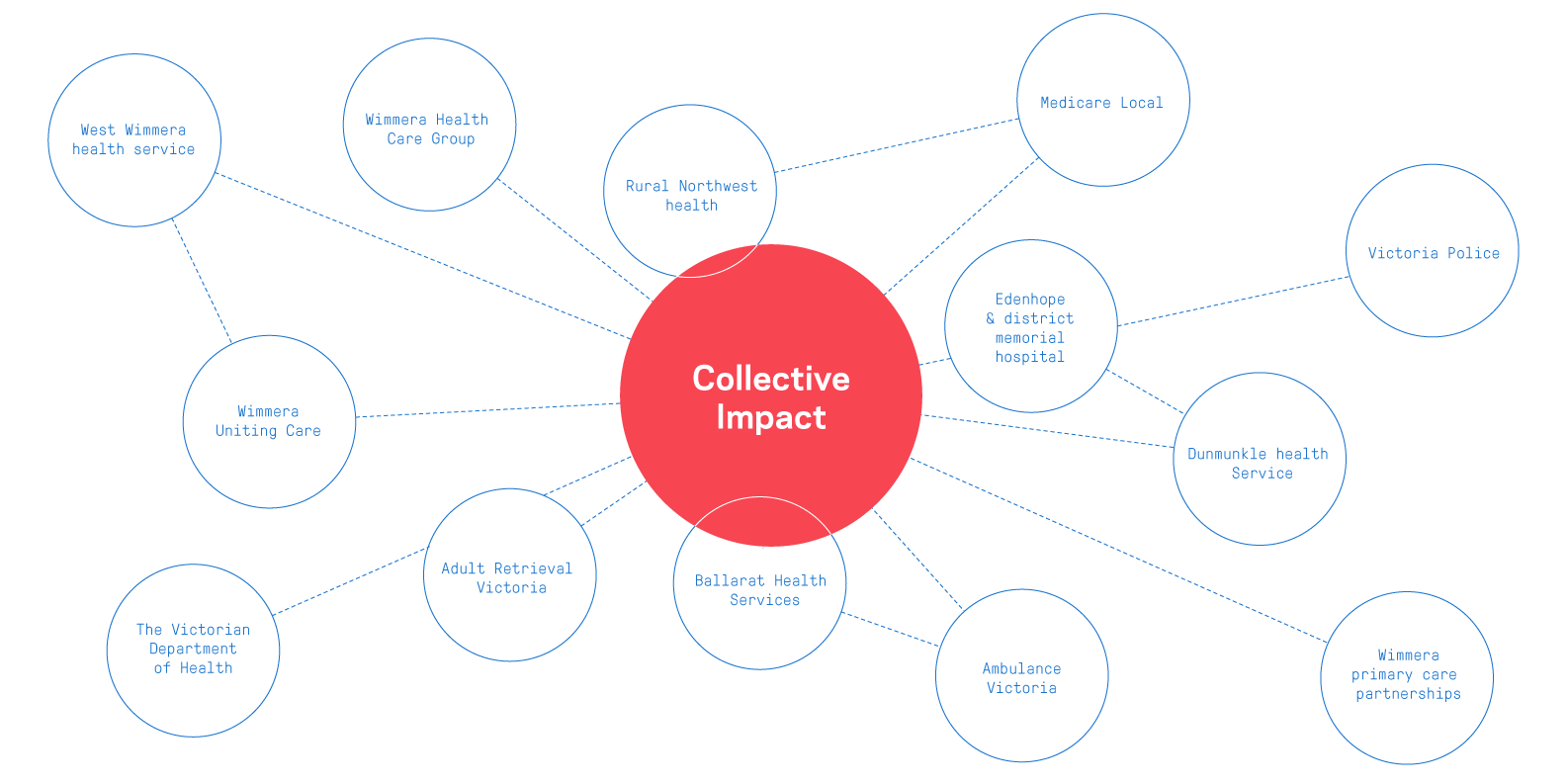

Your 92-year-old mother needs a simple but urgent procedure. The only vehicle available to take her to the hospital is the region's only ambulance. The nearest hospital is over an hour away. Now she faces a long night waiting for a check-up, before being transported back in the early morning. This scenario paints a common picture in rural healthcare. Smaller health care facilities are not equipped to handle a range of procedures directly, which puts pressure on other services such as ambulances and emergency rooms to provide care. It's an inefficient use of resources, and it's a tough experience for patients. Shifts in demographics, funding models, and increasing demand have combined to put emergency health services in regional areas under pressure. Hospital emergency rooms are stretched and everyday people are experiencing a diminishing quality of care. In an attempt to address these issues at the system level, THICK collaborated with a group of cross-sector stakeholders and Foresight Lane to establish a collective impact program for the Wimmera Southern Mallee emergency health services system.

PROGRAMM

THICK designed a two-day collective impact forum that brought together many of the organisations who are part of emergency services in the region. These groups included the Victorian Department of Health, five different hospitals and rural clinics, Ambulance Victoria, Medicare Locals, independent rural GPs and nurses. These stakeholders all wanted the same thing—to improve the delivery of medical emergency services to the community. The Victorian Department of Health was interested in distributing capability between different public providers to improve efficiency and efficacy. Individual hospitals were interested in relieving pressure on their emergency departments. Ambulance Victoria was interested in redesigning how they're managed between different emergency departments. And GP’s and Medicare locals were interested in redesigning referral pathways. All of the stakeholders were working individually towards improving the emergency health system. Yet they all faced similar obstructions: barriers to collaboration across industry or organisational boundaries, a lack of shared information and visibility, and a lack of a universal ‘system view’ meant their ability to improve the system independently was limited. Thick proposed that a collective impact process would be the most comprehensive way to drive positive change.

all images of the featured project are from thick.